Lloyd Reynolds: A Life of Forms in Art. A calligrapher’s life beyond letters.

“At that time Reed College offered perhaps the best calligraphy instruction in the country. Throughout the campus every poster, every label on every drawer, was beautifully handwritten… I decided to take a calligraphy class to learn how to do this…. If I had never dropped in on that single course in college, the Mac would have never had multiple typefaces or proportionally spaced fonts…and personal computers might not have the wonderful typography that they do”. — Steve Jobs, commencement address, Stanford University, 2005.

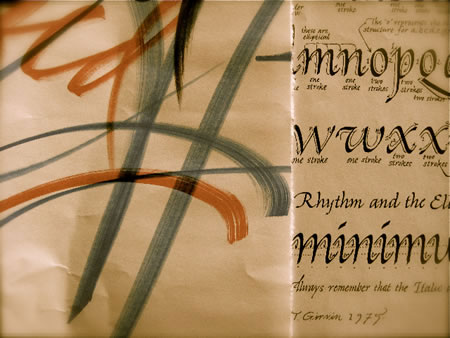

Elements of Reynolds’ poster

Elements of Reynolds’ posterAs Apple founder Steve Jobs suggested in that 2005 address, calligraphy’s importance extends beyond monks and type designers, and a big reason for that is Lloyd Reynolds (1902-1978), who created Reed’s celebrated calligraphy curriculum and also taught at Marylhurst, the Museum School (now Pacific Northwest College of Art) and in the Portland public schools. The Franklin High graduate became one of the best-known calligraphers in the world, named the state’s Calligrapher Laureate by Gov. Tom McCall.

An exhibition dedicated to a calligrapher might promise little more than rows of elegant lettering, but Reed’s new overview of Reynolds’ work, Lloyd Reynolds: A Life of Forms in Art, shows that his abundant art and life extended beyond letters.

It reveals a self-taught artist — hired to teach English and writing, he later discovered calligraphy in an old book — who absorbed ideas of useful beauty from pioneers like William Blake and William Morris and found multiple outlets for his creativity. Along with many of Reynolds’ hand-crafted tools, the exhibit showcases his detailed woodblock prints and etchings, posters, puppets, makeup and design for theater productions, and book designs. The few remnants of his “weathergrams” — seasonal poems inscribed on cardboard or paper and hung from trees — testify to the ephemerality of both seasons and art itself.

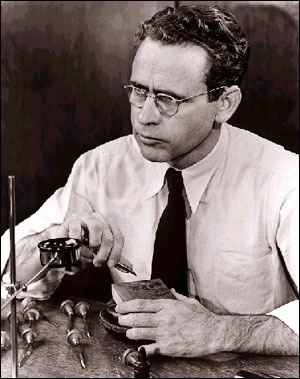

Lloyd Reynolds

Lloyd ReynoldsNot so Reynolds’ influence, thanks to his teaching. As Jobs noticed, Reynolds’ graphic design ideas permeated posters on campus for decades. And through his students, as diverse as poets William Stafford and Gary Snyder; composer Lou Harrison; type designer Sumner Stone; and screenwriter Ben Barzman, Reynolds’ humanistic artistic philosophy spread beyond the niche field of calligraphy, and beyond Portland. Those ideals, and his association with the Young Communist League, landed Reynolds before the notorious House Un-American Activities Committee in 1954. After he refused to testify, Reed suspended him for a summer, then relented when he explained himself to the faculty. A searing portrait he painted afterward called The Accuser glares out from that Red Scary time.

It’s no surprise Reynolds was engaged in issues of his time, because the exhibits reveal how much his art owed to his study of history, philosophy and anthropology. His correspondence and other writings on view here suggest that, for Reynolds, art was inextricable from culture and history. His own work has become a still-vital part of both.

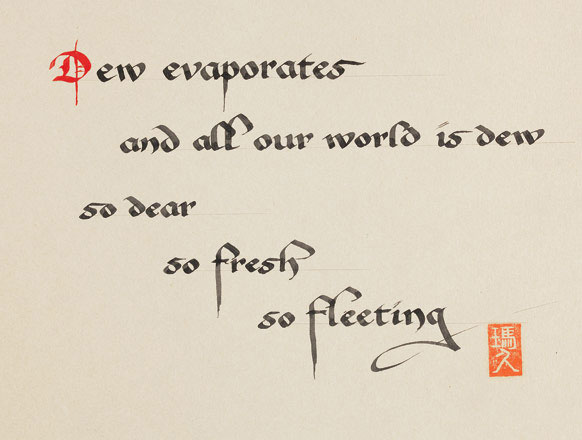

“Dew evaporates…” by Reynolds

“Dew evaporates…” by ReynoldsSource: Willamette Week