The Calligrapher's Secret

Exiled Syrian writer Rafik Schami recreates a cosmopolitan and pluralistic Damascus that existed as recently as 50 years ago, but that is so traditional in its way of life that it could be medieval.

If the vast and varied works that make up the literature of exile can be said to have anything in common, it might be in the way in which the exiled writer measures time. For the writer-in-exile, the past is most often understood not in terms of days, or years, but in terms of events, particularly those leading up to the moment of departure. For one author, the pivotal event might take the form of the invasion of a city, for another, a genocide, or expulsion from a village (or a garden), for still others, a natural disaster or a government coming into power. What is common to all of them is that the meaning and measuring of the past can only be understood in the light of what has happened. Time is now a matter of what existed «before,» and «after.»

The Syrian-German author Rafik Schami was born into a family of a Christian baker in Damascus in 1946, , and he remained in the city for some 25 years until he left for political exile in Germany in 1970. For Schami, it is the Damascus of the 1950s that has taken on this weight of «before time,» in the small but critical window between the departure of the last French forces and the ill-fated union between Syria and Egypt, a time in which the country was still in the process of deciding what it was going to become. Schami has described the period of 1954-58 as «the longest period of freedom that my country has had... a time of parliamentary democracy, several political parties, and newspapers. Not one single person sat in prison because of their opinion. It was a wonderful time.»

It is into this world of possibility that Schami casts the characters of his magical new novel, «The Calligrapher’s Secret,» a sprawling tale that is part mystery, part love story, part scathing political satire of Damascus corruption in all shapes and sizes, and always a nostalgic portrayal of the city Schami finally left some 40 years ago.

Like many great suspense novels, this one opens with a scandal: It is 1957, and Noura, the beautiful wife of the famous calligrapher Hamid Farsi, has run away. In an embarrassing and very Damascene twist of fate, her husband has unknowingly been commissioned to write ornately decorated love letters for the very man who has been trying to seduce her. To Noura’s horror, she begins to receive, in papers weighted to fly through the air and land on her balcony, love letters written in the calligraphy of her husband’s own hand. Yet very little in this novel is as it seems, and it will take some time before we understand who Noura and Hamid Farsi truly are, not to mention the man who has tried to seduce her, and still yet another man who finally convinces her to run away.

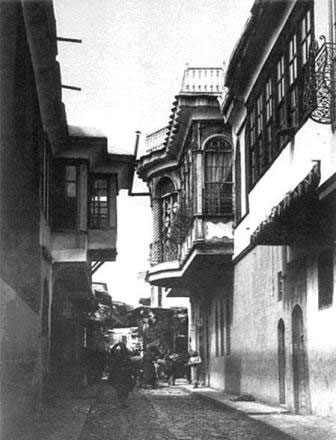

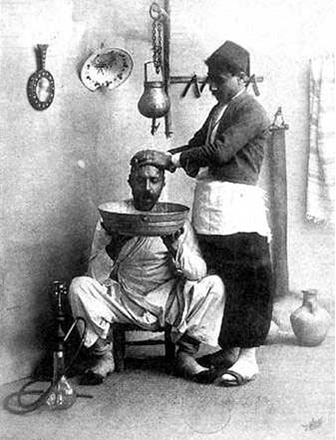

After this brief introduction into Noura’s plight, Schami casts us all the way back to her childhood, where in a whirlwind, 200-page tour of hidden alleys and old hammams, bakers and vegetable sellers, dressmakers and prostitutes, abusive husbands and lovesick boys of every religious denomination, and a single heroic dog, it soon becomes apparent that the city of Damascus is the most complex character of all.

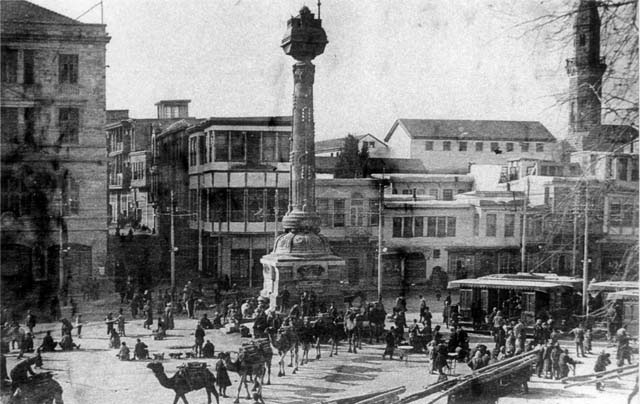

Like Schami’s previous bestseller, «The Dark Side of Love,» «The Calligrapher’s Secret» takes place largely in the neighborhoods around Straight Street, the most famous thoroughfare in Damascus: a wide road in the old city that traverses the Christian quarter of Bab Touma and the Jewish Quarter, eventually merging into the Muslim neighborhoods and markets around the Umayyad mosque. All of the neighborhoods along Straight Street, be they Christian, Muslim or Jewish, consist of houses nearly piled one on top of another, so that residents can quite literally peer from their windows into the neighboring streets and houses to acquire the necessary fodder for gossip.

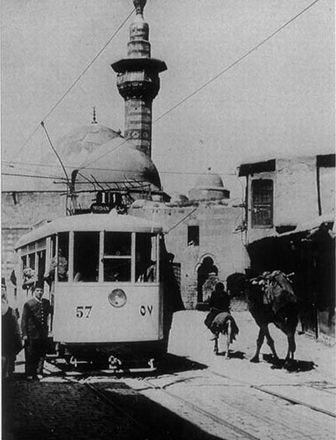

Schami brilliantly places the calligrapher’s house at the point on Straight Street where all three quarters intersect, and the novel magnificently captures a world that not so long ago was among the most diverse in the Middle East, where rumors fly from pharmacist to baker, from businessman to prostitute, cafe to cafe. In a country that has both resisted change and changed dramatically, the novel captures a pivotal moment before so much in the old city began to disappear: before the wealthy inhabitants moved to the suburbs and left the glorious, Ottoman houses to fall into disrepair, before the inhabitants of the Jewish quarter immigrated to Israel and America, before many of the Christians left Bab Touma to settle abroad, before the rise of the secular Baath party made the public practice of Islam more circumscribed than the colorful Sufi traditions that pepper his story. Indeed, it marks the last moment in Damascus in which a calligrapher could still be famous and revered throughout the city at all. One can almost envision each of these details slowly fading away, like the now-extinct tram that Noura rides back and forth through the city.

’I would have been a Jewish kid’

We could have no better guide to this multi-faceted past than Schami, a Syrian Christian who himself grew up in Bab Touma, and who once movingly pointed out that, «had I been born to a woman just seven meters away from my parents’ house I would have been a Jewish kid because our house bordered the houses in the Jewish Quarter in the West. Had I on the other hand been born to a woman 14 meters away, I would have been Armenian ...» A few chapters into the novel he introduces us to Salmun, a poor, jug-eared Christian boy without connections, who in his various jobs as a delivery boy takes us into the private courtyards of Damascus houses. Here we meet a dizzying cast of characters: widows who offer him exotic jams made of quince and rose petals, women who use the vegetables he delivers to concoct recipes to seduce their husbands, the beautiful, former wife of a Jordanian prince. It is through the character of Salmun that Schami really shines, and through him we witness the smallest details of life in the Christian quarter, complete with the «carts, bearers, horses, donkeys, beggars, and itinerant traders» that populated Straight Street in the afternoon.

Part of the joy, and the considerable frustration, in reading «The Calligrapher’s Tale» is letting go of the desire to remember every character’s history. Schami happens upon pedestrians in the street and regales us with their stories in turn: the sweetmeat seller Elias, the ice cream vendor Rimon, Yousef the grain merchant, Noura’s young Christian neighbor Maurice, to mention only characters who appear in the first chapter. (In chapter 2 he introduces five new characters in the opening paragraph — six, if you include the devil.). And yet we cannot let any of these characters fade completely, for one of the book’s miracles is that Schami only slowly reveals which characters are important, and they are very often the characters that we least expect. A cafe owner might be part of a nefarious plot to destroy the calligrapher’s reputation. The poor, Christian servant might have a heart big enough to capture the love of the calligrapher’s beautiful wife. Even Hamid Farsi, the seemingly selfish calligrapher, is more complex than he appears, for in time we learn that he has set out on a dangerous quest to reform the Arabic alphabet, heading a secret society dedicated not only to changing the appearance of the letters but to adding new letters and taking others away, an act many deem as a sin against Islam.

Schami’s novel can be read both as nostalgia for an easier past and as a harsh criticism of those elements of the society that resist reform. By the end of the novel, Hamid Farsi has two very different sets of enemies: the Pure Ones, a society of Islamic fundamentalists who refuse to allow Arabic, the language of the Koran, to be modernized, and the uneducated officials in the new government who don’t care about calligraphy or culture at all. Who is to say which group is more dangerous? Cringe inducing If Schami’s novel falls short, it is when he seems willing to pander to his foreign audience. Sentences such as «Calligraphy ...has a magical effect on an Arab» are cringe inducing, even when voiced by a foolish character. Schami can also seem a bit too relieved to be released from the constraints of Syrian censorship, and the lewd jokes and sexual scandals of the story can sometimes feel gratuitous (though in the age of Twitter scandals, one wonders if perhaps everyone on the street does have a secret to hide). Yet these are confined largely to the first part of the novel, and eventually the narrative takes over, to wonderful effect.

Perhaps Schami’s greatest accomplishment is that he has transformed the ancient literary device of the «frame story» known to English-speaking readers most often through «The Canterbury Tales,» but to Arabic speakers via «The One Thousand and One Nights,» into something strikingly relevant for a modern audience. The stories of Noura, Salmun and Hamid Farsi at the heart of this novel become in many ways simply occasions to tell other stories: those of the dozens of colorful characters living in the old city of Damascus. In this way he finds his place among an exciting new generation of Arab authors, many living abroad, who are revolutionizing the form of the novel to create a hybrid that is a fusion of novel and traditional Arabic storytelling, and in which the author shows his prowess by folding layers of stories one inside the other while always returning to a central narrative. Elias Khoury’s «Gate of the Sun» made waves when he used this form to tell the stories of Palestinian refugees making their way to Lebanon. The Lebanese-American writer Rabih Alemaddine’s recent masterpiece «The Hakawati» took the story of a man visiting his dying father in Beirut as the frame for telling not only the family’s history, but ancient tales ranging from «One Thousand and One Nights» to the Koran. Schami’s method is unique in that it feels entirely effortless: the juiciest stories here are simply those of ordinary people caught up in their lives.

And yes, there is something eerie about reading Schami’s novel as thousands take to the streets of Syrian cities to protest the rule of Bashar Assad. The novel is both an escape into a quieter time, and a reminder of what Schami could never have envisioned as he wrote this book: just how quickly everything can change.

Source: Haaretz