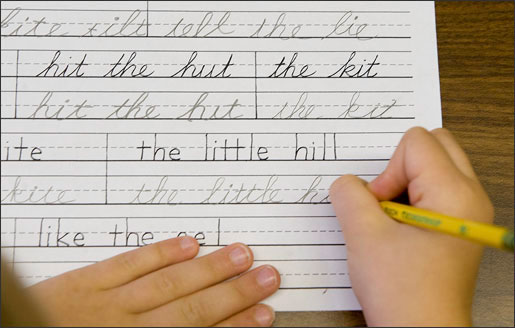

New standards don't require students to learn cursive writing

The Common Core curriculum, used in Indiana and 45 other states, does not include teaching cursive writing. Critics say schools should continue to teach cursive because it is used for practical purposes, such as signing checks.

The Contemporary Museum of Calligraphy follows latest developments in the US education reform.

Walk into any school these days and the kids aren’t working on their loops. They’re in keyboarding class.

Cursive writing and handwritten letters are the past. Keyboarding, emails and texts are the now — and the future. Indiana’s school curriculum now reflects that.

This month, Indiana joined a growing list of states that no longer require schools to teach cursive writing. Instead, Indiana will mandate schools to teach keyboarding in elementary school.

«I think it’s progressive of our state to be ahead on this,» said Denna Renbarger, assistant superintendent for Lawrence Township schools. «There are a lot more important things than cursive writing.»

The national move away from cursive is being fueled by the Common Core curriculum. That is an effort led by governors in 46 states, including Indiana, to agree to common standards and, eventually, common tests to measure whether kids are learning them. Cursive is not part of the Common Core curriculum. Keyboarding is. Lawrence Township, Renbarger said, saw the Common Core standards coming years ago and has transitioned class time away from cursive and toward keyboarding.

Victoria Linde, a sixth-grade student at Skiles Test Elementary School in Lawrence Township, said she learned keyboarding beginning in third grade. She and her mom, Kristin Peoples, see typing as the way of the future in a world in which emails have long replaced letters and texts are quickly supplanting the jotted-down note. Peoples, who types far more often than she writes by hand, is OK with the move away from cursive. «It sounds more effective to me,» she said. «Kids use computers more today.»

Still, not all parents — or even educators — agree that cursive should go the way of the slide rule. «I don’t agree with it,» said Jerry Long, who also has a sixth-grade daughter, Takita, who attends Skiles. «I think they should have the opportunity to learn all the skills they will need. How are they supposed to know how to sign their names?»

LaPorte, the retired teacher-turned calligrapher, said cursive is not merely an art, it’s a practical skill and one that — even if not required by the state — still can and should be taught by schools.

«If you practice for 10 minutes a day, and that can be squeezed into the curriculum,» she said, «it teaches fine motor control and discipline. It’s something every child can be successful at. But it does take practice.» Linne Hurley, whose daughter is a sixth-grade student at Lawrence’s Indian Creek Elementary School, also thinks dropping the requirement is a bad idea.

She wonders how today’s children will read handwritten notes from their elders or historical documents. «It’s something that’s going to be lost,» Hurley said.

Still, she only needs to look at her daughter, Laura, to see the future. Laura isn’t especially fond of keyboarding — and in fact when she writes, she pulls out a notebook and pen. But her notebooks are filled with . . . printed words. «I haven’t written cursive in years,» she said.

How much time to devote to handwriting — print and cursive, has been a hot debate for more than two decades, said Deborah Corpus, a literacy expert in the Butler University College of Education.

Corpus was a curriculum coordinator in Washington Township schools in the mid-1980s when statewide tests first began demanding writing skills in elementary grades. Before that, elementary «writing» instruction was mostly about writing the letters, not composition.

«Handwriting instruction takes a long time and lots of practice to get proficient,» she said. «Back then it was 30 to 40 minutes a day. Then it was cut to 20 minutes. Then to 15.»

Time spent forming print and cursive letters was crowded by the need to teach composition. Now keyboarding is crowding instruction even further.

«There is nowhere to buy the time and do all things well,» she said. «It’s been a trade-off instead.»

Corpus rejects many of the arguments for cursive instruction. She does not think learning cursive makes kids better learners or better writers, as some supporters argue. She’s not sure it’s a necessary skill for kids to have the way keyboarding clearly has become.

Still, she wants kids to be able to at least be exposed to cursive and be able to read it when they see it. «I don’t know exactly where I stand on this, to be perfectly honest,» she said.

Vanderbilt education Professor Steve Graham, a nationally recognized expert on handwriting, said some of the arguments for cursive are «romantic.» That said, schools have much to consider before junking cursive or cutting instructional time for handwriting.

Speed is important, he said, because slow writers can have trouble getting their ideas down — whether using cursive, print or a keyboard — and may be marked lower than they deserve when graded.

But there is no research consensus that there is any significant difference in writing speed for kids who rely mostly on printing or cursive, Graham said. And, in fact, many children develop their own «script» that is a hybrid of the two.

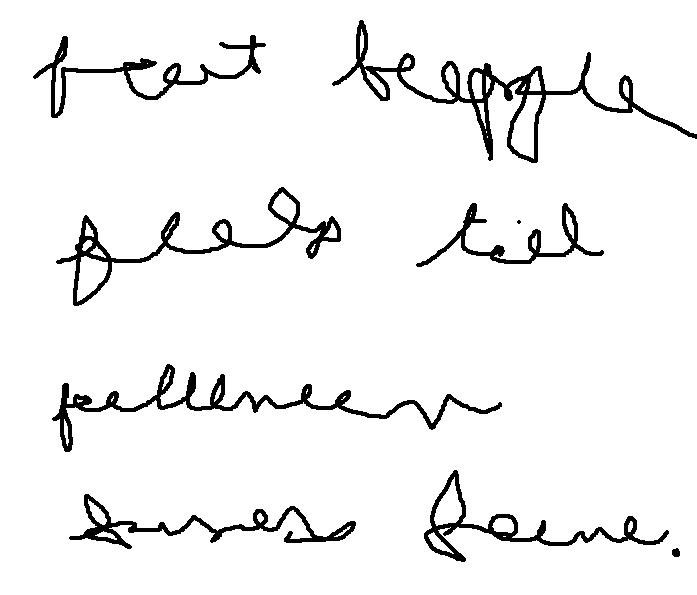

Even more important than speed, Graham said, is legibility.

Some studies show an edge in legibility for printing over cursive, but the larger concern is that students learn to write legibly in whatever style they are taught. The truth, he said, is that people make judgments about others based on their handwriting.

«It’s the same as when people look at a page with lots of spelling errors,» Graham said of illegible handwriting. «People think negatively about what you have to say. They question how smart you are. Teachers won’t muddle through. They start to say to themselves, ’This is not one of my better students.’»

The effect on the reader can be dramatic. In a study Graham has just completed but not yet published, he found that an «average» composition paper was often rated «poor» by test scorers if written with poor legibility. When the same average paper was written in excellent handwriting, it was routinely rated «above average.» «I don’t care if it’s cursive or manuscript, you need to be fluent and legible with at least one type of handwriting,» Graham said, «and you need to be fluent on the keyboard.»

LaPorte, who lives in Washington Township, taught cursive writing for 29 years in Indianapolis Public Schools, learning calligraphy along the way as a hobby. She later taught calligraphy at the University of Indianapolis. Her business, Hand Lettering for All Occasions, has felt the competition from printers and computers that can spit out professional-looking certificates and other documents that used to be hand-lettered.

But there are still many documents, such as fraternity charters that are too large for printers, or personal items, such as invitations and photographs, for which people prefer calligraphy as a personal or artistic touch.

Nonetheless, LaPorte worries for the future of cursive and its practical implications.

«It’s an art,» she said. «A vanishing art.»

Source: Indystar