From Russia, with Love

The International Calligraphy Exhibition, Moscow 2017

A year ago, I received an email from the Contemporary Museum of Calligraphy in Moscow, inviting me to take part in the International Calligraphy Exhibition to be held in September 2017:

‘We believe it a great flaw in our work that the British school of calligraphy and penmanship, as well as illumination and heraldry, has been scarcely represented in our exhibitions, and we’d like to improve that by inviting you to take part in our coming exhibition. Your works, together with Donald Jackson’s, would make a truly unique exhibit, something that people don’t get to see much here in Russia.’

The Contemporary Museum of Calligraphy was founded in 2008 by Alexey Shaburov, who runs the exhibition and convention centre at Sokolniki Park, north of Moscow city centre. As well as displaying a collection of calligraphy, the museum staff run adult workshops and do outreach work with children and groups with special needs. They are keen to show that calligraphy unites all cultures, east and west, and that it plays a part in well–being: self expression, stress relief and personal development. The exhibition, first held in 2008 in St Petersburg and roughly every 2 years since, is part of their mission. It takes place in a huge, very smart pavilion in Sokolniki Park.

Having arranged my trip and negotiated the complicated process of getting a Russian visa, I arrived in Moscow. As Donald Jackson was unable to attend I was the sole representative from the UK but I was met at the airport by Anastasia Moiseyeva from the museum, who helped me get my bearings in the city with her excellent English.

The 2017 exhibition, entitled ‘For Life’, displayed over 350 works by 150 contributors from 60 different countries. These ranged from the Far East, through Russia and the former Soviet Union, across the Indian subcontinent and the Middle East to all parts of Europe, North and South America and Australia. I was very impressed by the representation of so different many cultures, unified by calligraphy, and think that we can learn a lot from this in the UK, as a culturally diverse nation. It was also interesting to see that among the Russian calligraphers I met, there were an equal number of men and women, and that they tended to be young and very dynamic! The calligraphy pieces selected for the exhibition were not for sale and the museum acquires its permanent collection through gifts of the artists’ work.

Tim giving an interview for Moscow TV news (with translator), in front of the display of his own and Donald Jackson’s work.

Tim giving an interview for Moscow TV news (with translator), in front of the display of his own and Donald Jackson’s work.  Timothy Noad

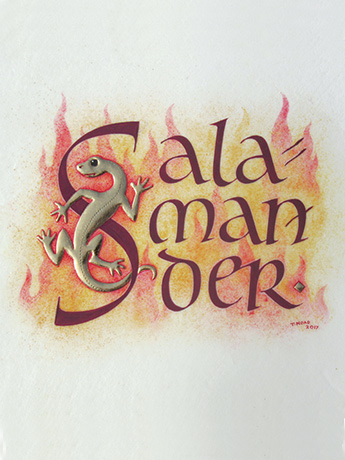

Timothy Noad‘Salamander’ In the medieval bestiary the salamander was said to survive unharmed in the flames.

Raised gold leaf on gesso, gouache and pen made letters on stretched vellum 7.5 x 10 cm.

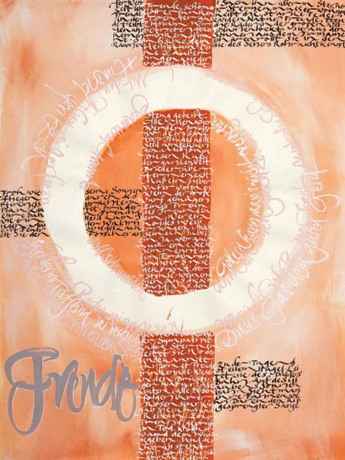

Katharina Pieper (Germany)

Katharina Pieper (Germany)‘Ode an die Freude’ (‘Ode to Joy’, from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony). Acrylics and gouache with brush, ruling pen and broad nibs on paper.

Maria Skopina (St Petersburg)

Maria Skopina (St Petersburg)‘The Feat of the Mercury Brig’, a famous Russian warship of the 19th century. A design with real movement and pzazz.

Pointed pens, gouache, automatic pen on paper

In the centre of the pavilion was a seating area where talks, demonstrations and workshops were held. There was an opening ceremony with speeches attended by VIPs from national and local government and other organisations. I was asked to give a PowerPoint talk about the work I do for the College of Arms and the Crown Office, as well as TV and press interviews. There were, apparently, rumours that I was a personal friend of the Queen and even that I taught her calligraphy! As I explained, the truth is that I am not commissioned directly by Her Majesty but am often asked to carry out works which are issued in Her name or presented to Her.

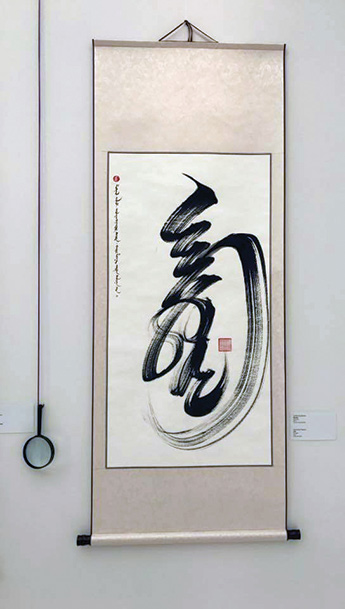

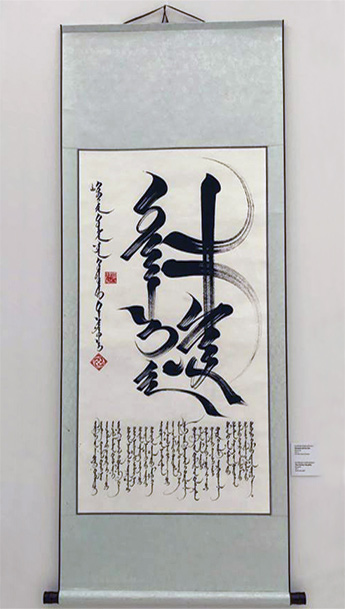

Among a handful of other international delegates were the highly regarded calligraphers Barbara Galinska from Poland and Maasaki Hasegawa, a Japanese born lettering artist who lives and works in Madrid. Katharina Pieper, who had taken part in the first exhibition with her partner, the late Jean Larcher, was represented by a piece in the exhibition ‘Ode to Joy’. There were also many pieces by non–Western calligraphers. The works from Mongolia, whose very name is a byword for remoteness, were some of the most eye–catching in the exhibition.

I was impressed by the work of Russian calligraphers, much of it dramatic and large–scale, like so much in that country. Although there are traditional elements, the practise of calligraphy is fairly new to them but increasingly popular. They have developed a wide repertoire of calligraphic scripts in which they are able to write Cyrillic, which in printed form primarily consists of what we would call upper–case letters. They are also very keen on the ancient ‘Vyaz’ style, in which the letters are elongated and contracted or nested together. This was outlawed in the 18th century by Tsar Peter the Great who, having seen western scripts while in Europe, introduced more Latin looking letters into the Cyrillic alphabet. However, Vyaz is enjoying an exciting revival in contemporary calligraphy.

As well as taking part in the exhibition I was able to spend a few days experiencing the city and sampling Russian delicacies: borsch, vodka and delicious chocolate! Tucked away behind Red Square I was fascinated to discover the Old English Court. This was the headquarters of the Muscovy Company, a group of English merchants who received their Royal Charter from Queen Mary and King Philip in 1555, the same year as the College of Arms.

When we hear about Russia it is often bad news. However, my visit to the International Calligraphy Exhibition was entirely positive and unforgettable. The people I met were friendly and enthusiastic; the works on display were inspiring and introduced me to areas of calligraphy I had never previously encountered. I hope to participate in the exhibition again and would encourage other calligraphers to consider having their work included, to further strengthen the calligraphic ties between the UK and Russia.

Timothy Noad HFCLAS

Tsengelbayar Sodnomoy, a traditional Mongolian calligrapher beside his work.

Tsengelbayar Sodnomoy, a traditional Mongolian calligrapher beside his work. Work by Tsengelbayar Sodnomoy (Mongolia)

Work by Tsengelbayar Sodnomoy (Mongolia)  Work by Anchbayar Erdenebatyn (Mongolia)

Work by Anchbayar Erdenebatyn (Mongolia) Ekaterina Volkova (St Petersburg)

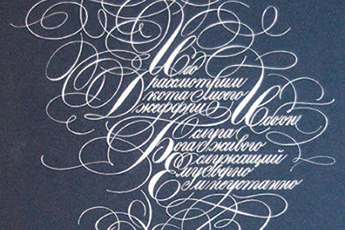

Ekaterina Volkova (St Petersburg)‘For I will consider my cat Jeoffrey’, an 18th century English poem by Christopher Smart, rendered into copperplate Cyrillic with brilliant flourishing and controlled execution in a complex design. Pointed pen in gouache on paper.

Dmitry Lamonov (Moscow)

Dmitry Lamonov (Moscow)‘The Birth of the Sun’ An incredibly accomplished and complex work by a graphic designer who aims to revive the use of Vyaz script in contemporary ways.

Broad and pointed nibs, ink on paper.

Olga Varlamova (St Petersburg)

Olga Varlamova (St Petersburg)‘The Battle of Navarino’, a sea battle in the Greek war of Independence, 19th century. A confident and dramatic combination of fine lettering and illustration with bold brush lettering.

Gouache, broad and pointed pens on paper

Yuri Shachnev (Murmansk)

Yuri Shachnev (Murmansk)‘It is the witness still of excellency to put a strange face on his own reflection’, from Shakespeare’s ‘Much Ado about Nothing’. Traditional Vyaz script in a subtle and evocative snow-like composition. Acrylic with a broad brush on canvas.

Source: This article was originally published in the Edge, Volume 23, Issue 4, Summer 2018. The Edge is the official magazine of the Calligraphy & Lettering Arts Society.