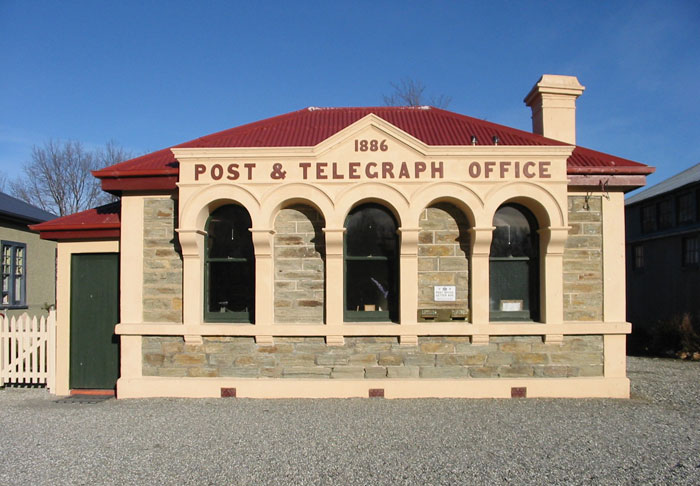

When the post office dies

Eternal instrument to deliver thoughts

Eternal instrument to deliver thoughts

The demise of the post office as a conveyor of monthly bills, pension cheques, charity-fodder and just plain correspondence has become a given. If the recent mail stoppage produced no more than mild, and temporary, inconvenience to all of the above, it also confirmed a much deeper truth: the pen, once mightier than the sword, has lost out to the byte.

We don’t write letters anymore; we e-mail them. Instead of the pen, we pound the keyboard as though that were enough to maintain the intimacy of a handwritten letter. Alas, it is not.

Keyboard has replaced the pen?

Keyboard has replaced the pen?

When the post office dies, there will be no viable way of getting letters to a distant receiver. No more stamps to buy, no more stationery, no more healthy strolls to the nearest mailbox, no mailmen to be protected from household pets or to tip at Christmas.

The Post still has its clients

The Post still has its clientsAbove all, we shall miss the most crucial element of our social intercourse, the personal touch. The keyboard is a tool. The pen is part of us. We hold it between our fingers.

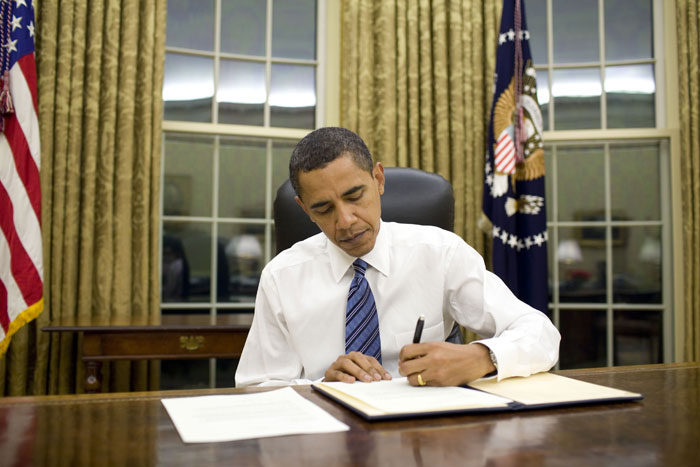

We transmit our feelings through it. Once we used to feed it, a fountain pen. We kept it privately in a drawer and took pride in our penmanship — an art that is no longer taught in our classrooms, though it must be admitted after watching President Obama wrestle his way, left-handedly and awkwardly, over his signature, that not everyone in high places has learnt it well.

President Obama signing papers

President Obama signing papersThere is a uniqueness to someone else’s handwriting that is at once pleasurable, and in its familiarity, comforting. It takes time to read; something the e-mail skimmer is denied. Friend, relative or colleague, the writing usually identifies the sender before the envelope is even slit open.

As for electronic mail, all that it has in its favour is that it is swift, and generally spontaneous. The response is immediate, only minutes after the original missive has been received. One doesn’t ponder over an e-mail. The object is to deliver it as speedily as possible so as to leave more time to dig deeply into the deluge of nothingness that is awaiting you in the inbox: the ghastly jokes forwarded by a thoughtless colleague, the family photos, the ads for the enlargement of certain body parts, what the papers are saying, and so on.

It’s also convenient in a way that the cellphone (or the iPad) is as close as the nearest purse or pocket, though it breeds in its users a snide contempt for all those who cling to the old ways, the snail-mailers.

What it gains in speed, however, it loses in privacy. What was once a private mailing is no longer so. Once sent, it is an open invitation to the most contemptible of all viruses, the hacker. The personal can quite readily become public; the e-mailer is never quite sure. The letter-writer on the other hand, remains smug about his certainty that no one else but the named recipient will read his thoughts. An envelope is a trusty lock.

The fact that snail mail takes days to deliver, even to a next-door neighbour, bestows on it the cachet of permanence. Private letters, as opposed to the electronic kind, are written to be kept — for future reference, the purpose of reply, or simply as a keepsake. How many long-married couples, for instance, have not discovered in a forgotten drawer a beribboned parcel of letters once exchanged in more innocent days when romance was interrupted by a forced departure — to war, to a distant university, or a business trip?

Robertson Davies

Robertson Davies

In the unforeseen event that one becomes famous enough to become the subject of a biographer, what a trove of information and insight such kept correspondence becomes. Whole volumes have been filled by the exchange of letters between writers who have something to say to each other, and by extension, the rest of the world outside. Our own Robertson Davies comes to mind in a volume of his own correspondence I came across a few years ago — an overflowing bowl of commentary and insight into literature, society and the ways of the world by someone who had plenty to say, and the good sense to preserve it.

Davies wrote with a pen. He is famous for his scornful put-down of another medium, the word-processor. «That,» he scoffed «is exactly what it does.» No more.

On the other hand my dictionary of quotations has plenty to offer in praise of the pen. Take Oliver Goldsmith: «No man was more foolish when he had not a pen in his hand, or more wise when he had.»

Source: Ottawa Citizen