We shouldn't write off handwriting just yet While keying has become the norm, it lacks personality

When it comes to penmanship, the handwriting is on the wall - although it may be too illegible to read.

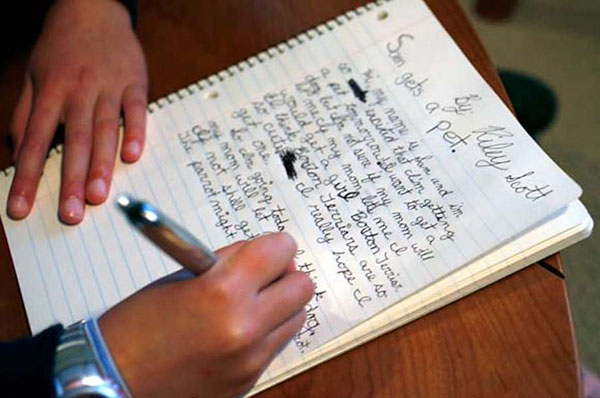

No longer do Americans grow up learning to master the slanted script that once united us in many forms of communication. Elementary schools have switched to a straightened-and-simplified cursive and give even that only a cursory treatment: Research shows that the amount of an elementary school day devoted to penmanship has withered, from an average hour per day a century ago to a measly 10 minutes today. Instead, students who've mastered tying their shoelaces move on to computer keyboarding.

Small wonder that when students take the college entrance SAT exam, which recently added a 25-minute handwritten essay, only 15 percent wrote in cursive. The rest printed in block letters.

The repercussions on the adult world are no less consequential. Most people admit a decline in their own handwriting attributable to a lack of practice. They eschew composing personal notes and letters, preferring the percussive rat-a-tat-tat of e-mails and text messages.

But they may be oblivious to the professional hazards of sloppy handwriting: a poor social impression, a doomed job application and tragic miscommunication. The National Academy of Sciences' Institute of Medicine, for example, has calculated that illegible doctors' writing causes 7,000 deaths every year because of misread prescriptions and orders.

Technology does, indeed, seem to be making handwriting as obsolete as smoke signals. But the demise of handwriting has been bemoaned before - prematurely, as it turned out. The Saturday Evening Post proclaimed handwriting an anachronism in an article in 1955, blaming "an increasing reliance on the telephone, typewriter, dictating machines and electronic brains."

Penmanship outlasted typewriters and Dictaphones, which are busily rusting in landfills from coast to coast. But those "electronic brains" - known in today's vernacular as PCs and Macs - are proving to be a more eviscerating usurper. The pen may be mightier than the sword, but the keyboard appears mightier than either.

While no one disputes the decline of handwriting, there is debate about whether this is necessarily a bad thing. Depending on whom you believe, waning penmanship is either a marker on our road to hell, or no more troubling that the obsolescence of Latin mass, 8-track tapes and Wite-Out.

We romanticize great writers of an earlier era, but they were creatures of their times, as we are of ours. "Were they writing today, Shakespeare would be blogging in iambic pentameter and Thoreau would be keyboarding his complaints about modern life on a computer that he assembled from spare parts," contended Dennis Baron, an English and linguistics professor at the University of Illinois, in an essay critiquing handwriting.

Historian Tamara Plakins Thornton, author of "Handwriting in America," considers the diminishing of penmanship inevitable - and no great loss. This may have some subliminal connection to the fact that a high school teacher once said Thornton's handwriting was so illegible that he could read it only because of his background as a code-breaker in World War II.

"Historically, concern that handwriting is becoming obsolete happens when we are anxious about our times. The underlying factor here is a concern that there's too much individuality at the expense of following the rules and conforming," she said. "It's as if we equate poor penmanship with moral laxity." She may be on to something here, given that the word "character" in Greek meant merely a written symbol, until Plutarch first applied it to human traits. Thornton likens handwriting to swimming, arguing nobody needs precision strokes, just enough proficiency to stay afloat.

California education standards still require penmanship instruction - printing in kindergarten, cursive in third grade - although many teachers don't regularly grade it and the state doesn't test to evaluate whether students are mastering it. For that matter, a new study by Steve Graham, an education professor at Vanderbilt University, found that 90 percent of primary teachers nationwide report receiving little or no formal training in how to teach it. So most concentrate on more creative pursuits - and subjects monitored by standardized tests.

"It's been such a struggle," said Shannon Scott of Petaluma, father to fourth-grader Riley and second-grader Brady. "I don't want to see my kids spending a lot of time in class on handwriting when it could be obsolete in a few years."

His wife, Teri, an art history major, is wistful for her grandmother's day, when people cherished fine penmanship for its beauty. "I don't think they spend enough time on handwriting. I was on the school site council arguing that students at this age don't need more computer time."

Riley, an avid writer who has filled notebooks with her narratives, loves personalizing her script, dotting her "i's" with hearts. "I like writing my notes and rough drafts in pencil because it feels like the best way to get my thoughts out," she said.

Not so for Brady, who likes to compose lyrics for the band he dreams of creating. "They wanted me to use a pencil, and that was a pain," he said. "He quit writing music for a month," his mom said, "Then we caved and let him keyboard."

We've come a long way since Colonial America, when elaborate cursive was the very mark of high education, and a discerning colonist could tell the gender and occupational level of a letter-writer merely by looking at letters. By the early 1900s, the nation was moving toward a uniform script. Teachers of the famous Palmer method functioned rather like drill sergeants, training the kind of hand-eye coordination skill that would prove invaluable to industrial America's factory floors.

As society sped up, streamlined penmanship styles came into vogue, banishing fussy flourishes and cutesy curlicues in favor of easier, less tedious skills. Today's popular programs deploy puppets, modeling clay, wood blocks and simple songs to help children master their letters (The ditty "If You're Happy and You Know It" becomes "Where do you start the letter? At the top! At the top!") One such program packs its premise in its name: Handwriting Without Tears.

Traditionalists mount a persuasive defense of old-fashioned penmanship - citing some research, for example, suggesting that students who master fluent cursive do better in school and score slightly better on their SAT essays.

Vanderbilt's Graham notes nearly a dozen studies confirming that legibility affects grades. In one 1992 study, essay graders scored neatly written essays 4 points higher on a 100 point scale - and even when they were trained to disregard neatness, they subconsciously awarded an extra 2.5 points on penmanship. He also argues that handwriting is a building block, necessary to advance children's ability to compose with confidence and take notes in class.

Special education students, in particular, may benefit from the kinesthetics of forming letters.

Others complain that when writers use a computer, they are too tempted to cut-and-paste other published material. Nor do they leave behind a written record of their thoughts - the sort of marked-up manuscripts that historians relish perusing because all those strikeouts and word revisions reveal volumes about a writer's thought process.

Handwriting requires only a pen or pencil and a piece of paper or a napkin - no machinery, no batteries, no electricity. Handwriting consultant Michael Sull of Mission, Kan. - hired for such writing gigs as the Academy Award nominations and Steven Spielberg's wedding invitations - has noted that penmanship is always with you, like breathing.

Finally, it conveys a personal touch that cannot be duplicated on the keyboard. Meaningful thank you notes and love letters simply are not word processed in Times Roman font or laser printed to perfection. They are an organic flow of emotion from heart to hand to paper.

But technological advances are knocking down penmanship defenses like bowling pins: The spread of laptop computers, for example, makes it easy to take notes via keyboard.

Even the personal signature, the apex of written individuality, may become passe in the business world, replaced by a 9-digit pin code that is more difficult to forge.

Most writers find the computer makes it easier to polish text, moving of whole paragraphs or the striking of entire sentences with a couple of keystrokes. Researchers at Boston College concluded that students who used computers wrote more rigorous essays by keyboard than by hand - even without tools like spell-check. Whereas handwriting slows authors down, keyboarding keeps pace even when their brains are firing like Gatling guns.

Even penmanship preservationists acknowledge an uphill battle. Teri Scott teaches at a Catholic high school, and with 107 essays to grade, she insists they be word-processed. "I know it may seem hypocritical," she said, "but if they write longhand, their essays aren't legible enough for me to read."

Still, reports of the death of penmanship, like that of the author with a beautiful hand who signed himself Mark Twain, may be exaggerated, if for no other reason than this: Microsoft Windows Vista is touting improved handwriting recognition software. Eventually your computer will be able to read your cursive - even if no one else can.

We shouldn't write off handwriting just yet While keying has become the norm, it lacks personality

We shouldn't write off handwriting just yet While keying has become the norm, it lacks personalitySource: www.sfgate.com