Virtual Exhibition of Spiritual Texts "VISUAL MUSIC: CALLIGRAPHY AND SACRAL TEXTS"

Henry Luce III Center for the Arts & Religion in Washington, D.C., previously closed because of the pandemic, has organized an exhibition of works by some of the world's most celebrated calligraphers.

On August 31, 2021, Henry Luce III Center for the Arts & Religion* opened a virtual exhibition of spiritual texts titled "VISUAL MUSIC: CALLIGRAPHY AND SACRAL TEXTS"

Among the invited participants are several exhibitors from the Russian Museum of World Calligraphy.

Among the exhibits there’s one work from the Calligraphy Museum's collection.

This work is discussed in detail in English on these two pages:

1) Psalm 92 by Abraham Borschevsky

2) Biblical Hebrew Poety and the Art of Repetition

The exhibition is curated by Jonathan Homrighausen, a Ph.D. candidate in Religion (Hebrew Bible) at Duke University.

* Henry Luce the Third is a philanthropist and publisher of TIME Magazine.

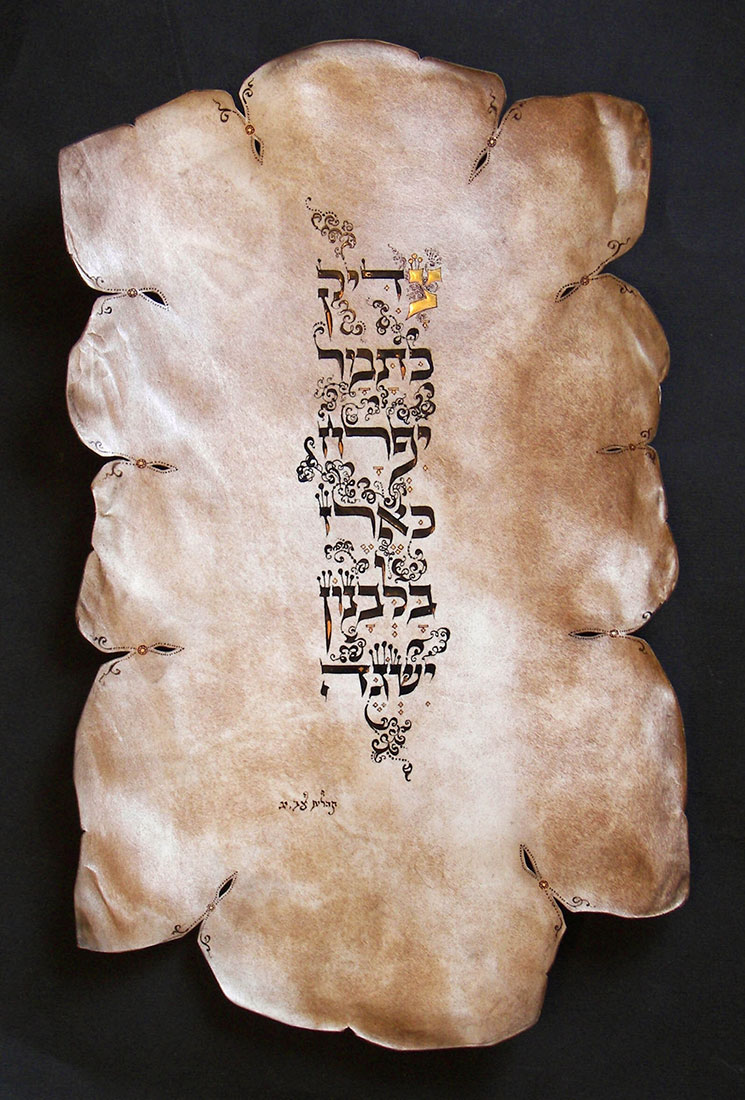

Abraham Borshevsky, Israel

‘The righteous will flourish like a palm tree, they will grow like a cedar of Lebanon, 2007Verse 13 of Psalm 92,

8½ x 14 inches (22 x 36 cm)

Natural calfskin vellum, handmade, glossy black soifer ink, copperplate, 24K pure gold leaf and gold paint.The Jewish calligrapher Abraham Borshevsky was born in the USSR and immigrated to Israel. He creates highly artistic Hebrew calligraphic works as well as works of Jewish ritual calligraphy (CTaM) with religious meaning. He writes mezuzahs and Torah scrolls according to rabbinic instructions.

This masterpiece of calligraphy includes a verse from Psalm 92:

The righteous will flourish like a palm tree, they will grow like a cedar of Lebanon. (Psalm 92:13).In this psalm, which is traditionally recited every Sabbath, the psalmist affirms faith in the power and goodness of God in helping Israel. The metaphor - the righteous are like a tree with strong roots - occurs several times in the Psalms (as in the first psalm). Even for those who do not read Hebrew, Borshevsky communicates the meaning of these words by forming a composition on parchment.

A hallmark of biblical poetry in Hebrew is repetition and variation, which scholars often call 'parallelism'. The righteous are like trees, and the letters Borshevsky uses are formal and visually straightforward. They go back stylistically to the Ashkenazic Stam script, used by Jewish ritual scribes for Torah scrolls. Because of this, to the Jewish eye, the letters themselves look sacred even before they are read. Since such writing is only used for holy texts, whatever is written by it continues on into eternity, beyond the mundane. Here Borschevsky also uses a metaphor: the biblical date palms are known to live for centuries and the cedars for millennia. Borschevsky goes on to let the letters sprout patterned like leaves. He also gives the parchment itself the outline of a large leaf. In this way, not only the righteous blossom and flourish, but also the letters that describe them.

The Torah scroll uses the same script, written only in special, absolute black ink. But here Borshevsky inlaid some letters with copper paint. The master gilded the upper right-hand letter (Tsadi) that opens the verse, as well as all the vowel marks above and below the letters. From a biblical point of view gold symbolizes the Temple utensils (Exodus 25); but the fear of the Lord (Psalms 19:11) and the words of wisdom (Proverbs of Solomon 25:11) are considered more important than gold. By using gold to write words praising the way of the Torah, Borshevsky is simultaneously suggesting that God's commandments are as precious as gold and that the Torah is more precious than gold. And just as Judaism considers the Torah "the Tree of Life", Borschevsky adds that the copper inlay "may resemble the appearance of a tree trunk where there is no bark".

As I often write in thematic essays, biblical poetry is known for the structure of repetition and intensification within and between lines of verse. Here the psalmist repeats the same metaphor - the righteous are like a majestic tree - but changes and intensifies it in the second half: date psalms are long-lived and cedars even more so. Borschevsky repeats this visually by using tags* - small crowns above the letters - for several letters in the second half of the verse (lines 3-6 on this page). Tags occur only on certain letters in the sacred Stam script, and it is a happy coincidence that far more of these letters appear in the words "as the cedar of Lebanon shall ascend" than in "the righteous as the palm tree shall blossom". This happy "accident" allows Borshevsky to visually enhance the "royalty" of the second half of the verse by adding more of these ornaments, which in Hebrew are called crowns. "Crowns" on these letters echo the regal and sacred associations associated with cedar, as they were used to build the Temple in Jerusalem and King Solomon's palace.

Borshevsky's work demonstrates the calligrapher's ability to communicate purely visually, whether or not their reader knows the language in which they are writing. This kind of intercultural communication is an accepted phenomenon in contemporary calligraphy: English-speaking artists, for example, draw their inspiration from Arabic, Chinese and Japanese traditions, although few of them speak these languages.

*Taghi (from Aram. 'tagin' - crowns). "Pins" on these letters represent "tagi," a distinctive script element for Jewish ritual calligraphy scrolls such as the Torah scrolls.

*Tzadi - the gilded letter in the upper right-hand corner, has the numerical value of 90 in Hebrew, which is only natural, since this work was commissioned as a gift for the 90th anniversary of one prominent jubilee.