Brody Neuenschwander

作者的作品

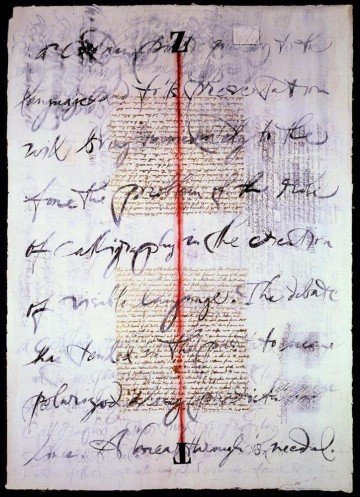

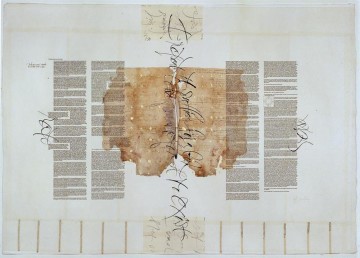

Z — T

Collage of rice paper on Rives BFK printmaking paper, with whitewash, Chinese ink, gold leaf, red chalk and lead letters, 75x105 cm, 2002Strong people and weak people

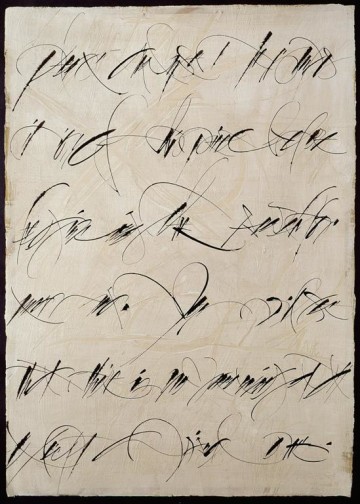

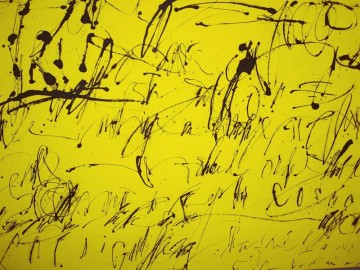

Collage of rice paper on canvas, with whitewash, gouache and Chinese ink, 420 x 100 cm, 2002Please analyse

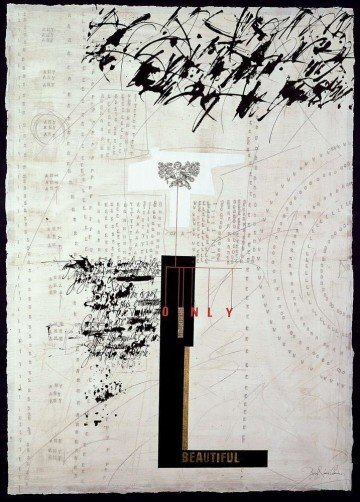

Collage of rice paper on Rives BFK printmaking paper, with whitewash and Chinese ink, 75 x 105 cm, 2000Only beautiful

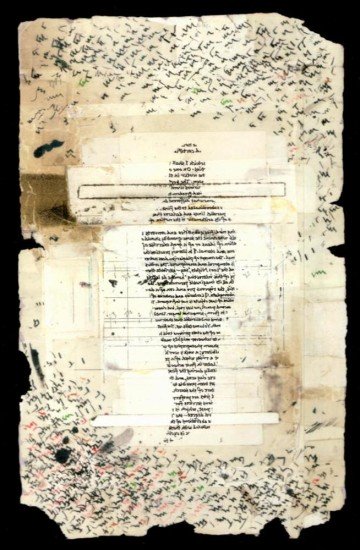

Collage of rice paper on Rives BFK printmaking paper, with whitewash, Chinese ink, gold leaf and gouache, 75 x 105 cm, 2002Don`t touch me. Sketch

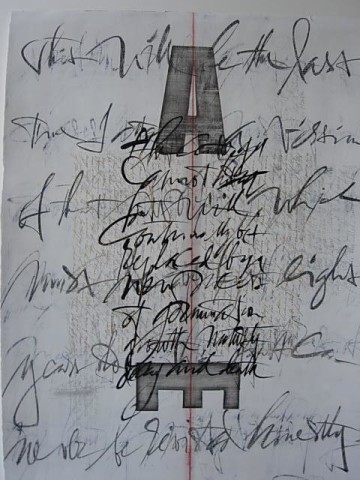

Paper cover sheet with pen trials and other marks made at random by the calligrapher, human form added as a film with microwriting, 210 x 297 mm, 2005Library of Babel

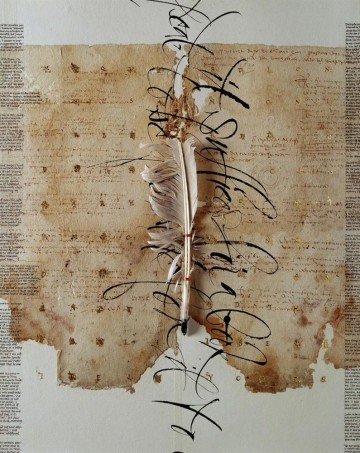

Collage of rice paper and old documents on Rives BFK printmaking paper, with Chinese ink and applied quill pen, 105x75 cm, 2000Library of Babel. Detail 2

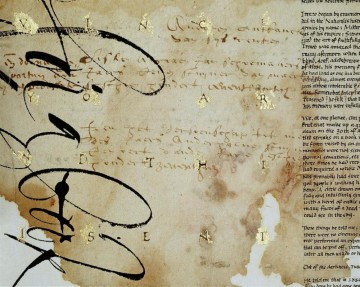

Collage of rice paper and old documents on Rives BFK printmaking paper, with Chinese ink and applied quill pen, 105x75 cm, 2000Library of Babel. Detail 1

Collage of rice paper and old documents on Rives BFK printmaking paper, with Chinese ink and applied quill pen, 105x75 cm, 2000生平

Brody Neuenschwander was born in Houston, Texas in 1958. His eighth year was spent in Germany, and it affected him profoundly. He learned a new language and a new culture, something that made him a bit of an outsider when he returned home. Neuenschwander returned to Europe as often as he could, eventually developing a fascination bordering on obsession with medieval culture.

As might be expect, his interest in calligraphy grew from his interest in history. As a teenager he was William Morris reincarnate, making manuscripts and tapestries, armor and wall paintings with a monumental enthusiasm. At Princeton University he was appointed University Scholar, a position that allowed him to devote almost all his time (when he wasn’t rowing) to art history, graduating in 1981 with high honors for his thesis on the techniques of medieval manuscript illumination.

Neuenschwander went straight from Princeton to the Courtauld Institute in London, where he completed his doctorate on the methodology of German art history in 1986. At the same time he studied calligraphy at the Roedhampton Institute. The cross-fertilization that resulted from doing academic and practical studies at the same time has influenced all his subsequent work. The objects studied by art historians are, for Neuenschwander, things that were made by human hands. The structure of the atelier and the properties of the materials are as important to him as the social context of their creation.

Neuenschwander began his professional career as assistant to Donald Jackson, an English calligrapher living on the Welsh borders. For a year Neuenschwander did repetitive studio work, mostly traditional ceremonial pieces. This allowed the techniques he had learned in London to become completely internalized. But it also allowed certain doubts about the validity of calligraphy in modern culture to surface.

In the years that followed Neuenschwander began asking fundamental questions about calligraphy. What is it? How is it used? Where should it be headed? What models should we be looking at?

As luck would have it, this was the very moment that his long collaboration with the English film director Peter Greenaway began. Greenaway, who wanted Neuenschwander to provide live-action calligraphy for the film “Prospero’s Books”, grilled him on the nature of his art. “Can calligraphy be charged with emotions and historical associations? Can it represent in visual terms sound patterns of the language? Can it explore the tense region between text and image?”

These were, of course, the central questions. In subsequent collaborations (“The Pillow Book”, “Flying over Water”, “Bologna Towers 2000”, “Columbus”, “Writing to Vermeer” and so on) the implications of these questions would be worked out.

The second force that pulled Neuenschwander’s work out of the orbit of traditional calligraphy was the German theoretician Hans-Joachim Burgert. Neuenschwander met the German calligrapher at a workshop in London. By default Neuenschwander became Burgert’s translator for the weekend. As a result, Burgert asked him to translate a lengthy text on the esthetics of calligraphy into English. This allowed Neuenschwander to come to a deep understanding of Burgert’s theory and has led to this theory being studied and adopted by other calligraphers in the West, such as Thomas Ingmire.

Burgert’s theory is essentially a classic German Gestaltungstheorie. Letterforms are subjected to formal analysis and judgment. Traditional Western standards of good and bad are replaced by a new formal language, one that is much closer to the esthetic judgments inherent in Arabic and Chinese calligraphy.

For Neuenschwander this new theory was a revolution. Suddenly the calligraphy of the East, which had always exerted an enormous attraction, could be analyzed and understood, not linguistically, but visually. The image-nature of these writing systems could surface.

Neuenschwander has studied the esthetics of Arabic and Chinese calligraphy ever since. Though he might be accused of a typical Orientalist attitude, he attempts to circumvent this danger by applying all lessons learned from the study of Eastern calligraphy to his Western writing.

In 1989 Neuenschwander met Nadine Le Bacq, who would become his wife in 1991. They moved to her home town Bruges in 1993, where they now live. Contact with Flemish language and culture has profoundly influenced Neuenschwander’s work. Though the Flemish are in many ways as tradition-bound as the English, their arts are not. It has been necessary to re-evaluate language and its visualization in terms of the very dynamic culture of Flanders.

Neuenschwander’s work left all standard definitions of calligraphy far behind from about 1996. Though the mark of the pen is usually present, so are typographic letters, scratched letters, drawings, paintings and other images. His work is certainly complex, requiring the viewer to attempt an integration of different kinds of information. There is certainly a deconstructive aspect, as the question is posed again and again,” Is this an image or is this a text”.

In 2004 Neuenschwander spent a semester teaching text art at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. This sabbatical from the artist’s studio allowed him to do research into the origins of text art in the first quarter of the 20th century and to follow this development as it impacted on American art after the second World War.

His present studies are focused on using the work of artists such as Cy Twombly and Jessica Diamond to produce a theoretical basis for a modern calligraphy. It won’t be easy.